Army Basketball vs. McGill, 1924

This is a 1924 Pointer account of Army vs. McGill basketball played at West Point, NY in January of 1924. The full text is below, but you can also listen to a transcription here or watch an audiogram of the story on YouTube, embedded below.

Army Basketball versus McGill. Wednesday, January 2, 1924

As reported in the January 12, 1924 edition of The Pointer, p.4.

Christmas Leave had hardly ended when Army encountered her first Canadian court foe, McGill University of Montreal, Canadian intercollegiate champions. Army’s strongest men were in the line-up for the first time this season and rolled up an impressive 40 counters while the Canucks were occupied with placing a 14 on their side of the score-board.

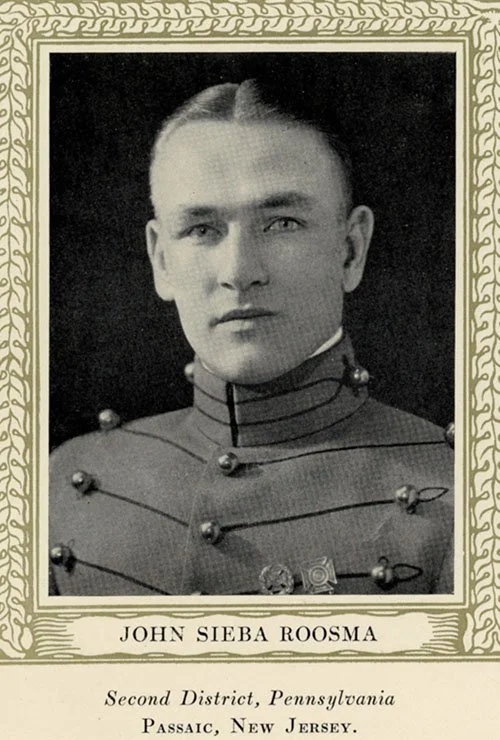

CDT Johnny Roosma

Class of 1926

It seemed like old times when the Army five took the floor and Bill Forbes and Johnny Roosma were espied among those present. Bill did not remain very long in the game but the seven minutes that he played were entirely sufficient to establish the fact that Bill has few peers in intercollegiate circles at running guard. As for Johnny Roosma, he is still the same crackerjack basketeer that he was last season; not much more praise can be given a basketball player. Another pleasing feature of the game was that Parker and Ellinger, who substituted for Forbes and Wood, played basketball of a higher calibre than they had shown previously this season. The other three members of the team, Dab., Strickler, and Vich., played like men possessed. If Christmas Leave was responsible it should be made a weekly affair.

Though the Army outplayed the visitors by far in the final period, Army’s banner half was the first. The team was working like a well-oiled and high class machine which totaled basket after basket. At one time such was its efficiency, that within fifty seconds four field goals were made. The Canadians displayed no offensive; they were too busy trying to hold down the rising tide of Army points. Mendelsohn, their star forward, found himself against a tartar in the person of Strickler and went through the first half without scoring a field goal. When the first twenty minutes were finished the score was 20-4.

In the second half the Army defense let down slightly; the offensive of the Cadets, however, suffered no let-up at all, Vichules and Roosma again caging three field goals each, while Parker repeated his two of the first period. In an effort to halt this successful offense, the McGill coach made numerous substitutions, but the final score of 40-14 shows how ineffective these efforts were. As it was, for the visitors, Mendelsohn at forward and Hilton at guard played excellent basketball until an excess of personal fouls removed Mendelsohn from the game in the second half.

Runaway, Boxcar, Potato Cadet

In the spring of 1957, West Point plebe Jerome Lee Gibbons did poorly on his Indoor Obstacle Course Test (IOCT), according to published sources. Fed up with being a cadet but afraid to ask his parents permission to resign, which was required at the time, he decided to run away. After a cherry ice cream cone in Newburgh, he headed west on foot to Campbell Hall, NY, where there was a rail yard.

Gibbons climbed into a boxcar he thought was heading upstate towards Syracuse near where he had grown up. That night the door of the boxcar was automatically locked and Gibbons was trapped inside. In reality, the Erie Railroad train was heading south to Jersey City. When it got there, the boxcar full of potatoes was parked, still locked. Gibbons was trapped for eight days!

Source: New York Daily News, March 27, 1957.

Without water and in the dark, Gibbons banged on the walls of the refrigerated car but nobody heard him. He nibbled on a few spuds but did not care for the taste. He also had a few cigarettes with him. He reported later that the sound of rainwater on the outside of the car nearly drove him crazy. Eventually, the car was opened by a trucker looking to load up for a delivery and was shocked when Gibbons tumbled out begging,

”Water! Water!” The dramatic story of his imprisonment was carried by newspapers across the country.

Soon, military police from West Point came and retrieved the AWOL cadet and brought him to the hospital. He was nursed back to health on a liquid diet and then solid food. Other than losing 15-20 pounds, Gibbons was in pretty good shape. He was dismissed from the USMA Class of 1960 and became a member of the Clarkson Class of 1861.

Ice Carnival king and queen at Clarkson, 1961. Source: Clarkson University Archives. Used for education purposes.

At Clarkson, Gibbons excelled as a civil engineering major and seems to have become quite popular on campus. He was in a fraternity, involved in many clubs, and was even voted the Ice Carnival king. He graduated in 1961 and got a job with Union Carbide, seemingly a good job.

Newspapers show he got a speeding ticket in November of 1861 and then tragedy. Early on the morning of December 15, 1961, Fulton’s sports car struck a concrete abutment on Grand Island in a single-car accident, and the young ex-cadet was killed. He was survived by his parents and a brother who served in the Marines during the war in Vietnam. A sad ending to a crazy runaway cadet story.

19th Century Meal Calls

Meal calls at West Point in 1853.

Meal calls at West Point in the 19th century were not what you might expect. In 1853, USMA regulations specified the following times and signals for meals:

7 A.M.: “Peas-upon-a-trencher, the signal for breakfast”

1 P.M.: “Roast-beef, the signal for dinner.” This was used on the Titanic and other ships into the 20th century for meal calls.

Videos of both calls are linked below:

Peas-upon-a-Trencher

Roast Beef of Old England (fife and drum)

Roast Beef on the Bugle as played on the RMS Olympic [skip to 5:40]

Dracula & West Point

Henry Irving and Helen Terry. Source: Archives, Calvin College

On March 19, 1888, as the East Coast dug out from one of the worst blizzards of the century, a train carrying a unique group of passengers made its way north from Weehawken, New Jersey to the Military Academy at West Point. Onboard were some of the world’s most renowned Shakespearean actors, including famed British thespian Henry Irving, later to become the first actor to be knighted, and the legendary Ellen Terry.

Irving was a dominant figure in the theater world in the last quarter of the 19th century as both an actor and as manager of London’s Lyceum Theatre. In Britain and around the world, Irving oversaw the production and direction of classical English plays while also acting in key roles. His portrayals of Hamlet, Macbeth, and Shylock played to packed houses.

During trips to America, Irving became acquainted with West Point through friendships with Colonel Peter Michie and other professors, and he and Ellen Terry would sometimes vacation at Cranston’s Hotel, the preeminent established of the area. It was situated on the hill in Buttermilk Falls (Highland Falls) where the West Point Museum and Five Star Inn are today. On an earlier trip to West Point, Irving had told Michie that he wanted to do a performance for the cadets at the Academy. When the 1887-1888 residency at New York City’s Star Theatre — 13th and Broadway near Union Square — came about, Irving reiterated his interest to Michie. Academy leaders elevated Irving’s request to the Secretary of War, who, to everyone’s surprise, graciously agreed.

The logistics of such a performance were complicated. Irving wanted cadets to come to New York City, but the Academy refused to let cadets miss classes and thought it was a risk to discipline. A matinee was also rejected because of the loss of class time. In the end, Irving agreed to close down the Star Theatre for the night of March 11, 1888, at great expense, and bring his entire troupe and sets to West Point.

New York City during the Blizzard of March, 1888. Source: Library of Congress

And then the blizzard struck.

Between 10 and 60 inches of snow plus winds reported to be 100mph in some places created huge drifts that crippled transportation and clogged the streets of cities from Maryland to Maine. For days, New York City was paralyzed, as was the Hudson Valley. A report out of Newburgh says 4’ of snow was common.

At West Point, 15-foot snowdrifts clogged the Barracks sally port and forced the Academy to cut food rations in half as deliveries became impossible. Marching to meals in formation was suspended because the paths through the snow were barely one person wide, and cadets took to jumping out of upper-story barracks windows into snowdrifts for fun. The West Shore Rail tunnel under the Plain was also blocked by snow and a Utica express train stalled in the snow at West Point, shutting down the line for days.

After several days, Irving worked with train officials and managed to arrange a special 4-car train that left Weehawken at 2:30 pm on March 19th for West Point. They were helped in the effort by General Horace Porter, USMA Class of 1860, who had been president of the West Shore Railroad, the line used to get to West Point. As Grant’s former personal secretary, Porter had influence.

The rail company was only able to spare four cars for the entire company of actors, musicians, dressers, and staff. Two cars for the gentlemen, a parlor car for the ladies, and a baggage car made up the special train. Irving’s dog “Fussy” accompanied the players. But the storm made it impossible to bring sets.

Grant Hall, West Point’s mess hall. Source: USMA Archives.

A small platform had already been erected in Grant Hall, the mess hall, by Irving’s crew, and the troupe had practiced on an equally-sized space. Behind the stage, British and American flags were hung and a makeshift curtain was arranged. Two limelights brought by Irving were used. These were the spotlights of the day, creating a bright light by heating quicklime (calcium oxide) with a flame of oxygen and hydrogen.

The play was The Merchant of Venice. Lacking sets, signs were hung that indicated the location of a scene, such as, “Venice: A Public Place.” Academy furniture was changed scene-by-scene. Tables were removed and benches brought in so that all cadets and Academy personnel were able to gather for the special event. The Corps sat in the front rows, in uniform, by class.

Many cadets had never seen a professional play before and were enthralled. By March of any winter in the 19th century, cadets had been isolated for months, so the experience was quite a treat. Ellen Terry was known as a particularly charming performer and easily won the hearts of the room. She even visited the one absent cadet that night, a young man stuck in the Cadet’s Hospital.

At the end of the show, every cadet in the room spontaneously threw their hat in the air and cheered. This was a punishable offense without permission, but Academy leadership ignored the breach of regulation. Cadets demanded a curtain call by the players and Irving gave a short speech. Thrilled, he declared that “...for the first time the British have captured West Point!”

A couple of professors canceled assignments for the next day, but in finest West Point form, most did not. Life went on at West Point, but based on letters sent home in the days after the performance, the extravaganza was a memorable one for the Corps. Some of the letters were published in newspapers across the country.

So, Dracula. In attendance on that March night was the Lyceum’s business manager, Bram Stoker. Nine years after the West Point performance, Stoker would publish his novel Dracula, featuring a title character that would become world-famous in the 20th century.

Bram Stoker about 20 years after his visit to West Point. Source: National Portrait Gallery, London.

Born in Dublin in 1847 at the height of the potato famine, Stoker was a sickly child and supposedly couldn’t even stand for much of his childhood. He would have likely endured treatments such as bloodletting. His exact malady is unknown. The child of a civil servant and a strong mother, he eventually became well enough to get some proper schooling and managed to enroll at Trinity College, Dublin, where he was a mediocre student. After a couple of years, he too became a civil servant before graduating, but a year into his job, he returned to school and became an extracurricular powerhouse, a star on the rugby pitch and in meetings of the Philosophical Society.

Long interested in theater, Stoker began working on the side as a critic. He had become enamored with Henry Irving after seeing the actor years in Dublin. Stoker’s near-total infatuation with Irving has been written about by many biographers. In 1871, Stoker reviewed Irving in a production of Hamlet which the actor read. Irving invited Stoker to dinner and they became friends.

By 1878, Stoker had married and moved to London, where he became a manager and eventually the business manager of the Lyceum Theatre, which Irving took control of in the same year. For the next 30 years, Stoker and Irving would work together with the future Dracula author traveling with the troupe around the world. Stoker would eventually set two novels in America and Dracula features a prominent American character, Quincey Morris. Stoker’s job as the Theatre’s business manner can be seen in Dracula in the details that he put into the novel’s travel scenes.

Stoker biographers and Dracula enthusiasts commonly state that Irving was one of the strongest influences on the development of the character Count Dracula. First, Irving’s physical appearance is very close to the novel’s description of the Count, which differs from the 20th-century movie stereotype of the suave romantic:

His face was a strong, a very strong, aquiline, with high bridge of the thin nose and peculiarly arched nostrils, with lofty domed forehead, and hair growing scantily round the temples but profusely elsewhere. His eyebrows were very massive, almost meeting over the nose, and with bushy hair that seemed to curl in its own profusion. The mouth, so far as I could see it under the heavy moustache, was fixed and rather cruel-looking, with peculiarly sharp white teeth. These protruded over the lips, whose remarkable ruddiness showed astonishing vitality in a man of his years. For the rest, his ears were pale, and at the tops extremely pointed. The chin was broad and strong, and the cheeks firm though thin. The general effect was one of extraordinary pallor (Stoker 1897, Chapter 2).

Sir Henry Irving Source: Library of Congress

Another connection between the Count & Irving relates to the actor’s personality. Writers have suggested that Irving’s management style was to use people to feed his ego. In other words, he could drain the life from someone.

So, on that March day in 1888, not only did the creator of Dracula visit West Point but so too did the Count himself, in a way.

Selected Sources:

“At Rondout.” The Buffalo Commercial (Buffalo, NY), Mar. 13, 1888.

“Snow-Plows Stuck.” The Times (Philadelphia, PA), March 15, 1888

Stoker, Bram. Dracula. London: Archibald Constable & Co, 1987.

Stoker, Bram. Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving - Volume 1. United Kingdom: Macmillan, 1906.

”West Point Captured.” Omaha Daily Bee (Omaha, NE), Mar. 21, 1888.

“A Unique Theatre Party.” The Sun (New York, NY), Mar. 20, 1888.

Where Did Cadets Live, Pt 2

In 1815, cadets moved to a new barracks, which after 1817 was known as the South Barracks! It was located on the Plain near the site of Ike Barracks today. It was demolished in 1849 or 1850. The structure was 180 feet long with three floors. It had two wings for officer housing/ offices (12 total) & 48 cadet rooms. 8 cadet rooms per floor, 3 floors, 2 sides. So a room either looked north or south. Each cadet floor had a narrow, covered porch with columns & railings. In the early days, there was a stairway for cadets in the middle. A later engraving shows spiral staircases on the outside.

An 1820 engraving showing the north side of the South Barracks. Source: Library of Congress

The building was rubble stone & mortar, meaning the stones were of various shapes/sizes. The roof was slate, which was rare in 1810s America. Original documents indicate skylights in the center stairway and the wings, but these are not shown on later engravings.

The location of the demolished South Barracks on a map of modern West Point.

Rooms were 14’ x 10’ with wainscoting, whitewashed walls, and a fireplace. Fires were apparently common and each cadet room had a bucket if a bucket brigade was needed. Cadet were required to keep the fender up in front of a fire and could be punished for not doing so. Later, by the late 1820s it seems, coal replaced wood. Still, it seems the South Barracks was very cold in the winter and hot in the summer. There was little ventilation because rooms faced either north or south with solid walls in between. There was a small window above the door as well as a larger, regular window. In the early years of the building, cadets were not provided furniture, so there would have been little standardization to chairs and tables. Beds were not universal with many cadets sleeping on mattresses on the floor. A musket rack hung on the wall.

The South Barracks had no plumbing. The privies appear to have been located to the south of the building. Later facilities were built behind the North Barracks (1817) next door. Water was supplied by a spring on the south side.

A digital recreation of a cadet room in the South Barracks based on available evidence.

Where Did Cadets Live, Pt 1

This is a summary of a series that first appeared on my Instagram account.

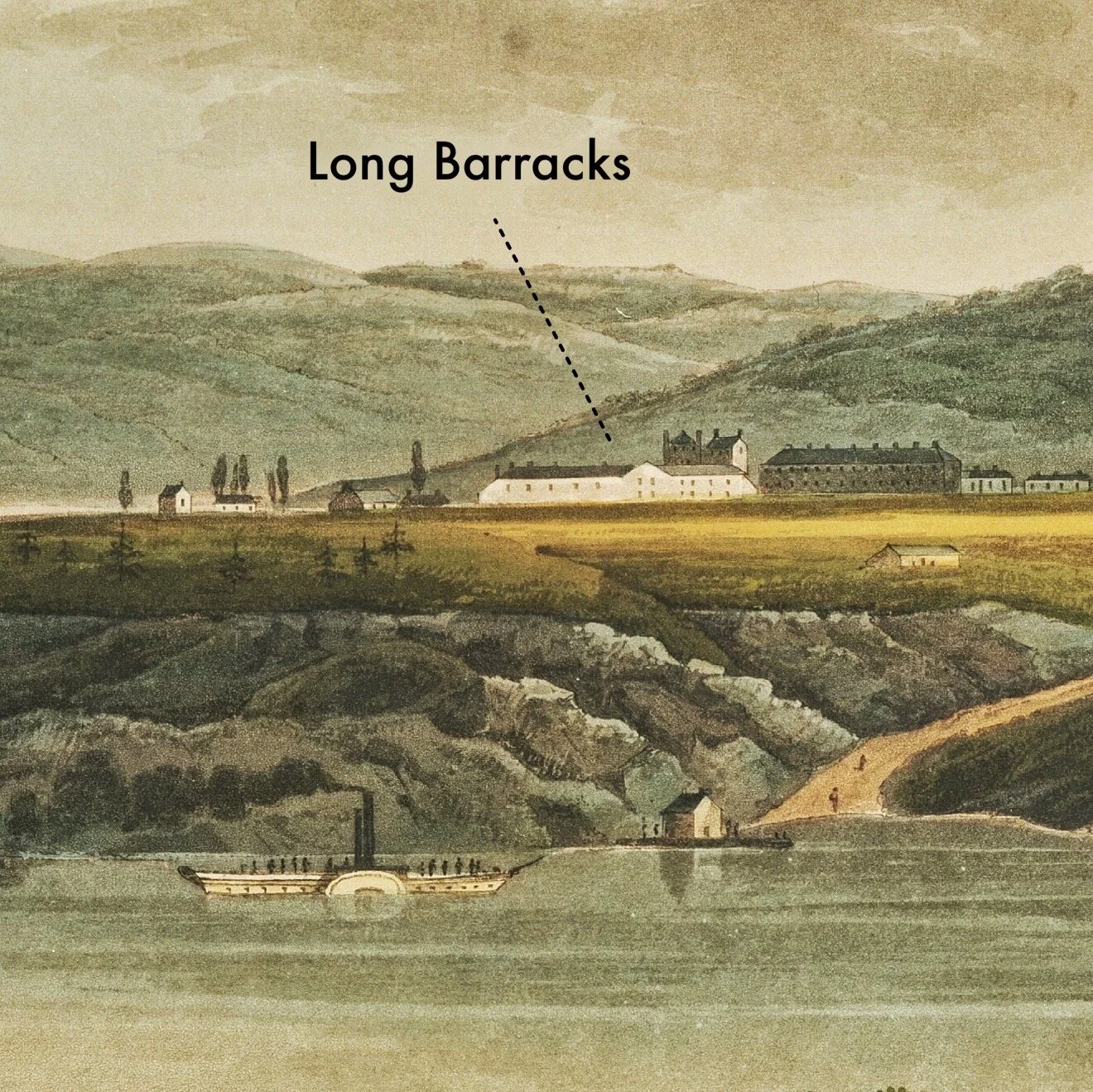

A fan of the site asked about where cadets lived over the years. Over a series of posts, we’ll explore the first century of cadet living. From 1801 until 1815, the main cadet housing was the wooden Long Barracks, aka the Yellow Barracks, on Trophy Point near the current Battle Monument. It was definitely painted a yellow ochre color at times. It predated the Academy & may have been built during the Revolution, but that’s a topic for another day.

The Long Barracks, as shown in an 1820s engraving by Milbert. Source: New York Public Library

The location of the Long Barracks in relation to current buildings. Base Map: Google Earth.

The Long Barracks was two stories with external stairs & stoops. On the western end was an addition used as a jail. The barracks had large basic rooms with open fireplaces. Cadets had to saw their own wood & retrieve water down the hill over the edge of the Plain in the vicinity of the band shell. Cadets occupied the upper floor & soldiers the lower. In 1815 cadets moved to new barracks & the Long Barracks were thereafter often called the Bombardier Barracks because artillery soldiers occupied it. Some families lived in it as well.

The Long Barracks based on an 1818 map. Source” Author

The Long Barracks burned early on the morning of 20 February 1826. Some histories get the date really wrong and say that the fire was in December or in 1825 or 1827, but the day is supported by multiple sources. For example, on the day of the blaze, the post Quartermaster Aeneas Mackay sent a letter to Quartermaster General Thomas Jessup:

I have the honor to report to you that about 5 O’Clock this morning the Barracks occupied by Company A of the 2° Reg of Artillery stationed at this post and the Military Academy Band, took fire and in the course of two hours was burnt to the ground.- February 20, 1826

There are also cadet accounts of the fire. The conflagration may have started in the guard room when a soldier fell asleep. The old wooden building was engulfed before a bucket brigade could even be formed. Cadets rushed to the scene & helped save the soldiers & families living there. No lives were reported lost! Cadet Albert Church recalled the following in his memoirs, and this is my favorite West Point quote of all time:

I think before a single pail of water was thrown upon it, the whole building was in flames, and with nearly all its contents, save the men, their families, and the largest and most confused collection of large rats that I ever saw, was consumed, even the guns of the soldiers in the guard-rooms.

A view of the Long Barracks in the 1822-1825 time frame. Artist: John Hill. Source: NYPL

Next in the series will be the old South Barracks!

Selected Sources:

Church, Albert E. Personal reminiscences of the Military Academy from 1824 to 1831 : a paper read to the U.S. Military Service Institute, West Point, March 28, 1878. United States Military Academy Library Special Collections.

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. "West Point at the Moment of Exercise" New York Public Library Digital Collections.

The Untimely Death of Cadet James G. Carter

The sad, accidental death of West Point Cadet James G. Carter.

The Cadet Monument, West Point, NY

Photo by Author

In the West Point Cemetery is the Cadet Monument, dedicated in 1818 to honor Cadet Vincent Lowe, killed on New Year’s Day, 1817. On the column of the monument are the names of other cadets who perished while at the Academy. One of these names is James G. Carter. His marker reads, “JAMES G. CARTER of Virginia. Died June 2nd 1835. Aged 18 yrs & 2 mos.” The story of his death is a sad and remarkable one.

On Monday June 1, 1835, Cadet Theodore M.V. Kennedy from Virginia, only 16 years old, was fencing with Cadet Carter in their room (likely North Barracks) without masks and without buttons on the end of the foils (or by one account the button fell off). Kennedy struck at his friend and the point hit below Carter’s eye. Kennedy ran screaming for help from the room and other cadets responded. Carter was found collapsed on the floor with a trickle of blood flowing from the wound. Although the injury looked minor, the foil had entered the brain. The surgeon was sent for and cadets put Carter on his bed and tended to him. He briefly regained consciousness but quickly fell into a delirious state what sounds like a coma. He died the next morning about nine hours after the accident. Kennedy was naturally quite shaken by the accident.

Cadet Kennedy never graduated. He became an artist and in 1838 traveled to Europe to study on the USS Brandywine. How did an artist get passage on a Navy ship? Perhaps it was not uncommon, but Kennedy’s father was naval officer Commodore Edmund Pendleton Kennedy (1785-1844), a veteran of the First Barbary War and the War of 1812. Kennedy was the first commander of the East India Squadron, set up in the 1830s to protect U.S. (economic) interests in East Asia.

Kennedy died suddenly in February of 1849 at Oden’s Hotel in Martisburg, Virginia (now West Virigina). He had been working on a painting the day before and had attended a party with friends that night. One of Kennedy’s friends was artist and future Union brevet Brigadier General David Hunter Strother, known nationally for his personal account of the Civil War and his humorous writings under the pseudonym “Porte Crayon.”

Cadet Carter also had famous relatives. One of his uncles was James Gibbons, called the “Hero of Stony Point” for his gallantry during the 1779 battle not far from West Point. Gibbons became a customs collector in Richmond and corresponded regularly with Thomas Jefferson.

Selected Sources:

Charleston Daily Courier. 6 February, 1849.

Evening Post (New York). 5 June 1835.

Melancholy Occurrence. Vermont Gazette,. 9 June 1835.

Naval. New York Daily Herald. 8 October 1839.

West Point, June 2. Charleston Daily Courier, 18 June 1835.

West Point Cadet's Polka, 1850

I’ve recreated the 1850 “West Point Cadet’s Polka” from the original sheet music for solo piano, published by Benteen in Baltimore. Please check it out and consider subscribing to my YouTube channel.

West Point Polka, 1847

In 1847, New York dance “professor” Pierre Saracco dedicated three dances to the cadets of the United States Military Academy, who he claims to have taught. Saracco was known for inventing dances and is credited with introducing a five-step waltz. The songs were composed by a Mr. F. Raggio, about whom I can find almost no information. Saracco had a dance studio at 50 Canal Street in 1847 and then at 110 Grand Street in 1849. He seems to have opened a satellite academy in Brooklyn in 1851. By the late 1850s, advertisements for his dance instruction appear in Buffalo and Philadelphia. I am not sure if he moved or franchised.

One of the three dances dedicated to cadets was the “West Point Polka,” which I’ve recreated for you at the video link below! The tempo is a guess, but is within the range of similar dances of the time. Enjoy, like, subscribe, and tell a friend.

"Blown to Atoms"

A gruesome account of a USMA graduate's death in 1888.

Warning: This post contains graphic details of a USMA graduate’s violent death.

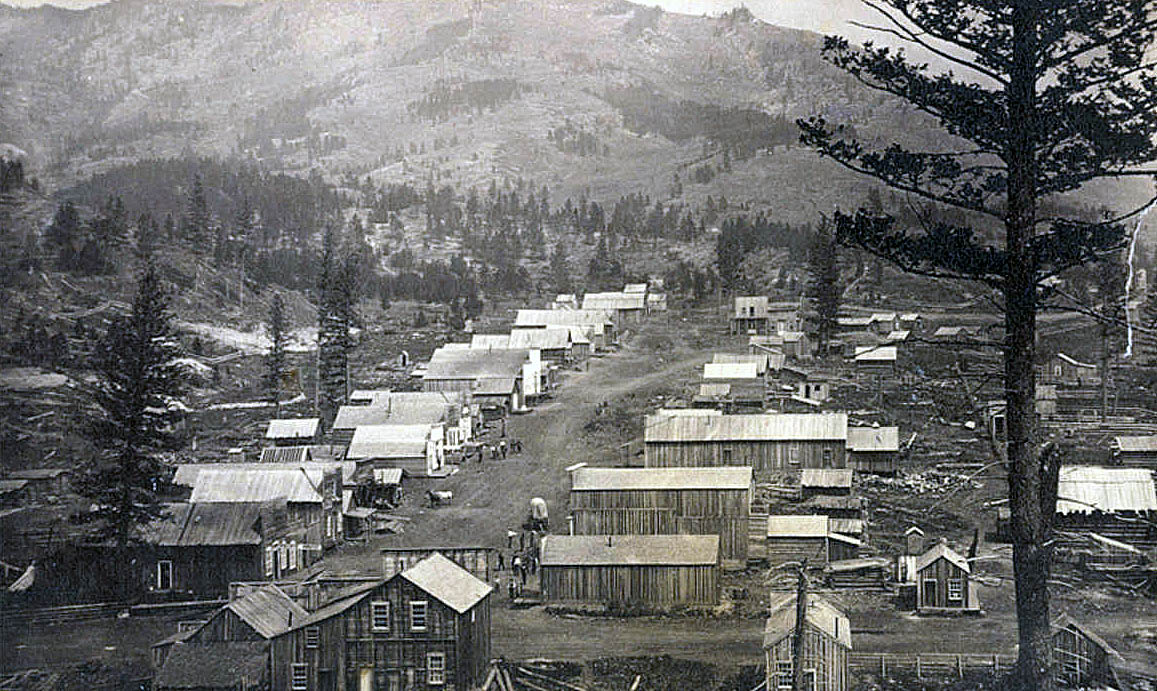

Maiden, Montana in the 1880s, Public Domain photo by William Culver. Source: Montana Historical Society.

Maiden, Montana is now a ghost town, but in 1888 it was an active mining community. Only seven years old at the time, the town was at its all-time population of 1,200 people in 1888. James Batchelder, USMA Class of 1868, was attracted to the boomtown. After West Point, he spent a short career in the West before going AWOL in 1870. His Army career ended the following year and he seems to have spent some time teaching and working for a railroad company. In Maiden, he was involved in mining and logging. In March of 1888, he was about to put his engineering expertise to work building a bridge under contract when his friends became worried about his whereabouts. Missing over a weekend, two of Batchelder’s friends (Archer and Lackie) hiked to his cabin on Monday. What follows is their gruesome discovery as reported in the Helena Weekly Herald in March of 1888:

After a climb of about two miles the cabin was reached when it was found that the building was badly demolished, and upon closer investigation the men were horrified to discover Batchelder's scalp and shreds of skin and flesh from his left arm banging over the ridge pole and the walls splattered with blood. A bed in the room was completely torn to pieces, part of which being literally ground to dust. As everything in the building was covered with the dirt and timber which had fallen from the roof, Archer and Lackie returned to town and got a number of men to help remove the debris.

Upon closer search the lower limbs, partially rolled up in the blankets, at the foot of the bed, one finger and thumb, a portion of one shoulder blade and a small section of the spinal column, which, in addition to the scalp and fragments of skin and flesh mentioned above, was all that could be found of the remains.

A coroner’s jury was empaneled, and after careful examination rendered a verdict that deceased came to his death by the explosion of giant powder. Cause unknown.

There was known to have been about five pounds of powder in the cabin at the time.

Pretty graphic for the 19th century! Batchelder was interred at Fort Maginnis but his remains were eventually moved to Custer National Cemetery. His Find-a-Grave page is here.

Source: "Blown to Atoms." Helena Weekly Herald, 15 March 1888.

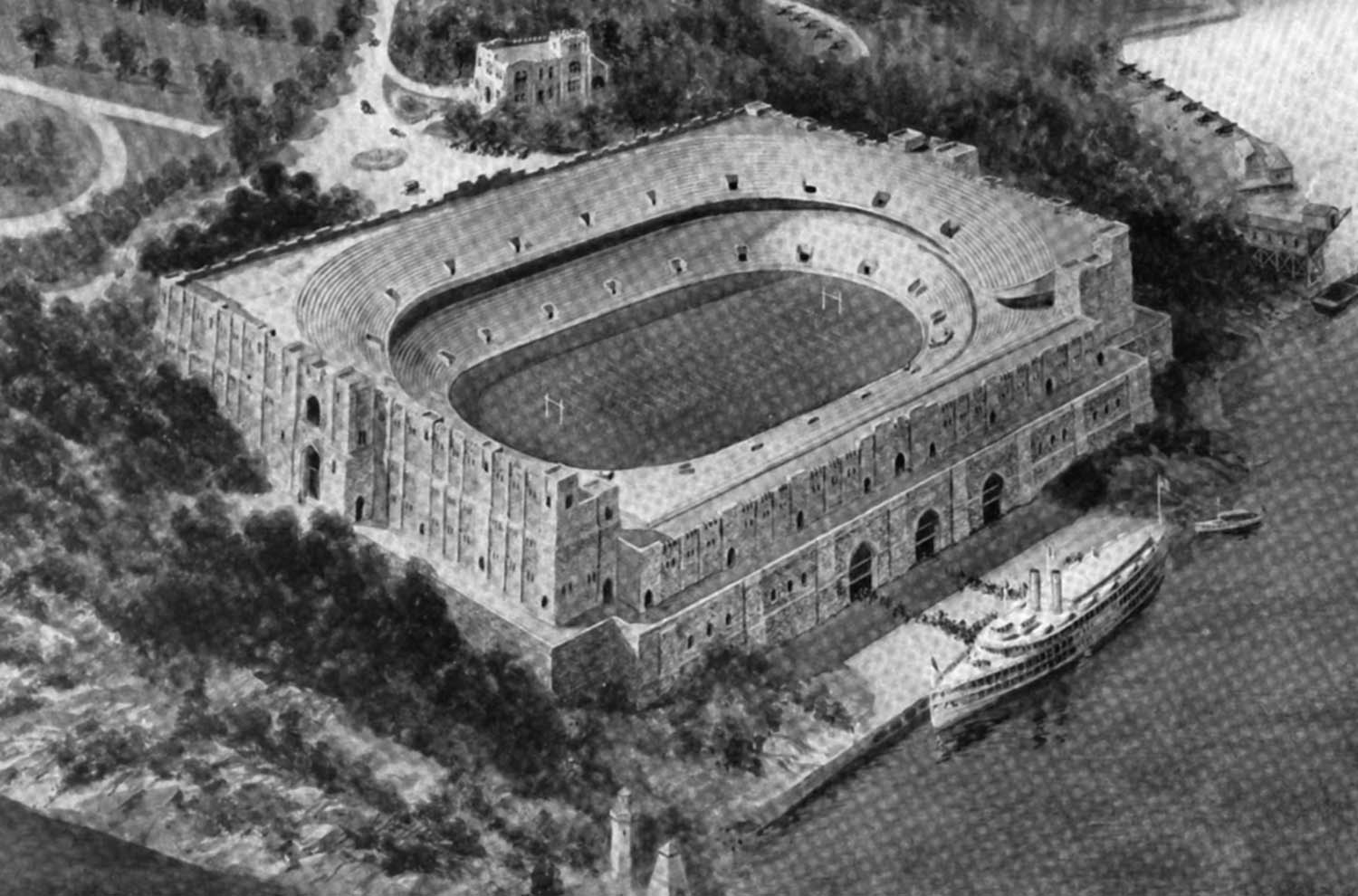

Stadium by the River

The proposed riverside football stadium at West Point.

I generally only write about West Point before World War I, but last week a USMA grad and Execution Hollow reader asked me about "MacArthur's Colosseum." The best evidence I have comes from an Infantry Journal article from February 1922. The article said about the proposed facility:

The construction of a public Colosseum or stadium at the Military Academy is proposed. It is to be properly arranged for football and other athletic sports as a means of promoting interest in athletics and physical development indispensable in students of the military profession.

The natural contour of slope to the river northerly from Fort Clinton is favorable to the reception of an arena surrounded by seats in horeshoe form providing accommodations for 40,000 to 45,000 spectators.

Construction upon this site will afford convenient access and direct entrance to spectators from a steamer landing at the water front.

The stadium is designed to be of concrete upon concrete and steel supports of a permanent nature.

A proposed football stadium on Trophy Point, as shown in a 1922 Infantry Journal article.

An illustration accompanying the story shows the two-level stadium nestled between Gee's Point (where two lighthouses stood) and about where the Kelleher-Jobes Memorial Arch stands at the end of Flirtation Walk. The architectural style maintains the Collegiate Gothic style favored by the Academy after the 1903 Architectural Competition. Passengers can be seen disembarking a steamer at water's edge.

As Michie Stadium was opened in 1924, the plan for a stadium by the water was likely never seriously considered for very long. The 1923 Annual Report of the Superintendent specifically mentions funding for a new football and baseball facility along the west side of Lusk Reservoir. Prior to Michie Stadium, stands were erected each fall on the Plain for football games. The 1923 report notes that this was unsightly, costly, and prevented the Plain from being used for training. In addition, crowds, and presumably ticket sales, could not be easily controlled because there was no fence. Michie Stadium was open and in use by the fall 1924 football season, although it seems like the contractors continued working until October of that year, a month after the planned completion date. Congress required paid admissions to defray the construction costs.

Sources:

"New Construction at West Point." Infantry Journal 20 (2). United States Infantry Association, 1922.

United States Military Academy. Annual Report of the Superintendent, 1923. United States Government Printing Office, 1923.

Drunk Middies, 1839

A group of Midshipmen try to sneak alcohol into the West Point Hotel

The West Point Hotel as it was depicted in an 1852 edition of Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion.

On the evening of August 31, 1839, First Lieutenant Miner Knowlton received an order from Superintendent Richard Delafield to "quell" a riot at the West Point Hotel on Trophy Point. Knowlton, given leeway to use "such force as it might be necessary to employ," rounded up a sergeant and eight men and set off to the establishment. As he approached, he was met at the gate by the proprietor, Jacob Holt, who urged him to hold off on sending in troops for the time being. Knowlton consented and entered the hotel with Mr. Holt and Lieutenant Benjamin Alvord. Inside, the officers found seven or eight men either drunk or "much excited by spirituous liquors" swearing loudly and causing a ruckus. Alcohol was forbidden on Post and at the Hotel at this time. The story that soon emerged follows:

At 9 o'clock that evening, the group arrived by steamboat at the wharf. They had with them one servant and a steamer trunk. The driver available to take them to the Hotel would not allow the trunk to be brought with them and demanded that they leave it for a porter. The men refused and proceeded to carry the trunk up the long hill to the Hotel. When they arrived, they went to the dining room and asked for the trunk to be sent to one of their rooms. Some of the men were already visibly drunk at this point. While at tea, the hotel management discovered that the trunk was full of booze and locked it up so the men could not get at it. A bottle was also found hidden in a cigar box carried by the servant. When the group of men discovered that their alcohol had been seized, several flew into a rage and demanded their property. A couple scuffles broke out, profanity was thrown about, and at one point, some of the men threatened Mr. Holt with their sword-canes! Mr. Holt, consulting with a Navy officer staying at the Hotel, determined that several of the trouble-makers were U.S. Navy Midshipmen with perhaps one from the Texas Navy.

A photo of the West Point Hotel later in the 19th Century. Source: NY Public Library

Eventually, 1LT Knowlton and men arrived and the rowdy Middies turned their anger at him, cursing the Army, the Post, Post regulations, and the Hotel. The inebriated carried on about property rights and illegal search and seizure. Some men challenged the West Point officers to duels. But, with the help of a couple less-drunk members of the naval party, Knowlton got a handle on the group. The trunk of alcohol was brought outside and eventually the rowdies were escorted to the wharf to wait for the midnight steamer to New York.

Beat Navy!

Sources: Academy records kept by the USMA Library

The July 4th Riot of 1800

On the Fourth of July in 1800, there was a riot between West Point soldiers and patrons at a local tavern.

On July 4th, 1800, before the Academy even existed as a formal entity, a bloody riot broke out yards from the post at North’s Tavern. A combination bar, restaurant, event hall, and hotel, North’s was located approximately at the corner between Bartlett and Taylor Halls, where the bridge goes over to Thayer Hall. The boundary of the Government’s property was less than 100 feet away! The public house was a source of periodic angst for West Point commanders and by 1798, an order was on the books that no soldier was to go there without written permission. To enforce this rule, patrols from the garrison would periodically check the tavern for violators. According to West Point officials, local patrons would often attempt to start fights with soldiers at North’s.

North's Tavern was located just feet from the southern boundary of West Point property. The establishment became Gridley's in the 1810s and was bought by the Government in 1824 to eliminate the temptation. It was after this that Benny Haven's became famous.

On that fateful holiday, a large group of people from the surrounding mountains had come to North’s to celebrate. Captain James Stille, the garrison commander at West Point, claimed to have seen fighting at the tavern that spread across the Post boundary. When he subsequently sent a patrol to check out the fracas, the soldiers were reportedly disarmed and bloodied by the partygoers. When a soldier reported that people were being murdered. Stille set off to the barracks to round up reinforcements for an orderly response, but on his way he was met by angry troops, muskets in hand with bayonets affixed, storming towards the drinkery.

Thomas North, the proprietor, told a different version of the same incident. He claimed that an armed soldier barged into a dance on the second floor of the inn and refused to leave when asked. When asked a second time, according to North, a fight broke out and the soldier shoved his bayonet at him. North deflected it and the soldier, John Quirk, tumbled down the stairs with a civilian who had grabbed hold of Quirk's musket. At the bottom of the stairs was an outside door where other soldiers were waiting. They soldiers charged forth with their bayonets and those in the tavern defended themselves with chairs. After a scuffle, the soldiers retreated and gathered up their comrades.

As the angry soldiers approached, the local revelers retreated inside and formed a defense line at the top of a stairway. Armed with weapons they had taken from the patrol as well as clubs and stones, a vicious fight commenced in the stairway. The soldiers were “beat back with lots of blood.” Stille appears to have ordered the soldiers to surround the house, but it’s clear a great deal of commotion took place. North claimed that nine windows were smashed as soldiers threw stones into the structure. Several patrons were apparently injured. Some women inside tried to escape the fight by climbing into the attic by way of loose floor boards. North also claimed that the soldiers trashed the bar and stole money and alcohol before forcing the innkeeper’s fourteen-year-old son out of the house at the point of a bayonet. Further, he alleged that the soldier mentioned above, John Quirk threatened to “bash out” his wife’s brains until another soldier came to her rescue.

After some time, Captain Stille was able to end the melee and several people were taken to the guard house for questioning. North claimed that Stille threatened to fire a cannon at the house if the remaining patrons did not surrender. In the end, it is unclear if any charges were filed. Stille wrote to Major General Alexander Hamilton for advice and the future Broadway star recommend turning over any unreleased civilians to local authorities and to be cooperative in any civil matters against soldiers involved.

You can read Stille’s letter to Alexander Hamilton here, and Hamilton’s response here. Thomas North's account can be read in the July 29, 1800, edition of the Poughkeepsie Journal (p.4), available through a subscription to Newspapers.com.

Getting to West Point, 1824

Albert Church's R-Day at West Point, 1824

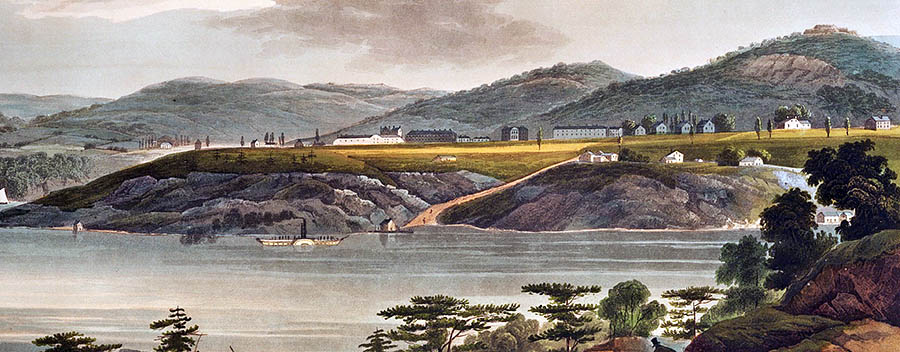

West Point ~1820. Source: NYPL Digital Collections

Last year, I posted the West Point arrival story of John H.B. Latrobe. Check it out here if you missed it. For this R-Day, I post the rather lengthy arrival story of Albert Church. Class of 1828 and future USMA Professor of Mathematics. Church was just 16 when he entered on a Sunday in June of 1824. At the time, there was no R-Day because cadets could not be expected to arrive on a particular day because transportation was so difficult. Instead, they were given a time period in which to report, so new cadets arrived in dribs and drabs. Church was from Connecticut. Years later, he recalled his first day:

Having failed to connect at Poughkeepsie with the only passenger steamer then running every other day on the river, I took my passage on a sloop, a regular packet for New York, with the promise that I should be landed at West Point, though this was not a prescribed landing place. This promise, better performed than many promises made nowadays, resulted in my being put ashore at 3 o'clock in the morning at Cold Spring, in a pouring rain. Wet to the skin, I found my way to a hotel, where I impatiently waited the coming dawn and then sallied forth, in search of transportation to West Point. At the wharf I found a small sail boat freighted with a pair of black horses, just ready to cast off. Stepping on board—myself and traveling companion lugging my blue chest, the modern army trunk was not then in vogue—we were soon set down on the North wharf, then the only one in use. A sentinel, in full uniform; the only human being in sight, brought me to, and required, me to write my name on a slate—a habit which for many years was strictly enforced on all coming to or leaving the Post. Upon making inquiry how we were to reach the Military Academy, for I had no idea how far we were to go, who said in a jocose manner, that we should have to walk, unless we could persuade the owner of the ponies to let us ride them up the hill. As for the chest, we could take that up ourselves, or leave it for the authorized porter, (an old soldier with one arm, the lost one being replaced by an iron hook suitable for his business,) no other person being allowed to transport baggage for hire; that he might be around in the course of the morning, but probably I should have to wait till Monday morning—a pleasant prospect for a fellow without a dry thread about him. By the way, I should say that I believe; these black horses were, at that time, and for two or three years after, the only span of matched carriage horses on the Point. They belonged to the Postmaster and were always, during these years, pressed into service to draw the various dignitaries who visited the place, up the hill, among others, in two instances, General La Fayette. At this time too, I think none of the Professors or Officers owned a horse. There wore no roads suitable for carriages scarcely so for horseback rides....

The sentinel having pointed out my way up the hill, old road still visible just below the present one, I crossed the plain diagonally, just after reveille, and passed between the two most prominent buildings of the academy, the North and South barracks, without seeing an individual, until I entered Gridley's hotel, a large two story wooden house on the edge of the bank, a little of northeast of the present new building for public offices [note: this refers to the 1870 Administration Building]. Here I found several other young gentlemen ambitious of military fame. This was the only hotel in the neighborhood, "where all visitors were entertained, except special official ones, who were cared for in the west end of the cadets' mess-hall, by Mr. Cozzens, the famous ancestor of the after Cozzens' hotel keepers. Having relished a good breakfast, four young aspirants took their way back and across the plain...

Having reported to the Superintendent and been received and questioned with that kind, yet unbending dignity for which he was ever distinguished, we were escorted by an orderly to the South Barracks, and the last three described were located by the cadet officer in charge of the new cadets, in a small room without vestige of furniture, with no place to sit except on the window sill, and left without a word of direction or advice, to discuss among ourselves what was to come and what we were next to do. Upon hearing a drum and a running to and fro, we concluded something of importance was going on, but had no idea whether it concerned us or not; until the cadet lieutenant, who had located us and so kindly left us to ourselves, rushed into the room and with an angry tone demanded, "Why do you not fall in?" Now I understood the meaning of the word "fall," but into what, or from whence, we were to fall I did not know. Of course we started forth and down the stairs we went, and came near falling, literally into a heap at the bottom. Fortunately, however, we fell into the ranks already formed for church, were faced to the right and told to "forward march." At my first move, I stepped squarely on to the heel of my forward file, when he faced about and with doubled fists threatened serious war, before I felt myself sufficiently educated for it. I took a backward step, not laid down in the Tactics, when those familiar cries, "pay attention," "close up," "what are you about there," had the effect of restoring order. Poor marching soon brought us to the chapel, where after a long preliminary service I listened to a dull sermon, one hour and a quarter long, the only lasting effect of which was to lay the foundation of that dislike, which I have ever since entertained, for long sermons.

The South Barracks, where Church was housed on arrival, had 48 cadet rooms, most holding three cadets. It was a gray stone building with a slate roof and verandas on both sides. This image shows spiral staircases up the front, but these were likely added after Church's era.

Upon leaving the chapel, with strong convictions that this kind of life was not suited to my taste, and that, doubtless, I had mistaken my profession and had better set out for home on the first arriving boat, I was cordially greeted by a cadet of the third class whom I had once before seen, who took me to his room and introduced me to his roommates, members of both the second and first classes. These cadets, instead of making me stand on tip-toe on one foot, tossing me in a blanket, or smoking me out, treated me with kindly interest, gave me correct information of what I was to do, and how to do it; in other words, treated me as a true gentleman ever treats his fellows, and thus seriously modified my resolution to go home. In the meantime, the rain which had been falling continually, ceased, the sun shone out brightly; on my return to my room I found my chest, got out of my wet clothes, and intelligently fell in for dinner with pleasant thoughts and coming appetite.

Church's entire memoir is available from the USMA Library here.

This map, a crop of an 1826 map by T.B. Brown, shows many of the locations mentioned by Church. Source: Library of Congress

Source:

Church, Albert. 1879. Personal Reminiscences of the Military Academy from 1824 to 1831: a paper read to the U.S. Military Service Institute, West Point, March 28, 1878. West Point: U.S.M.A. Press.

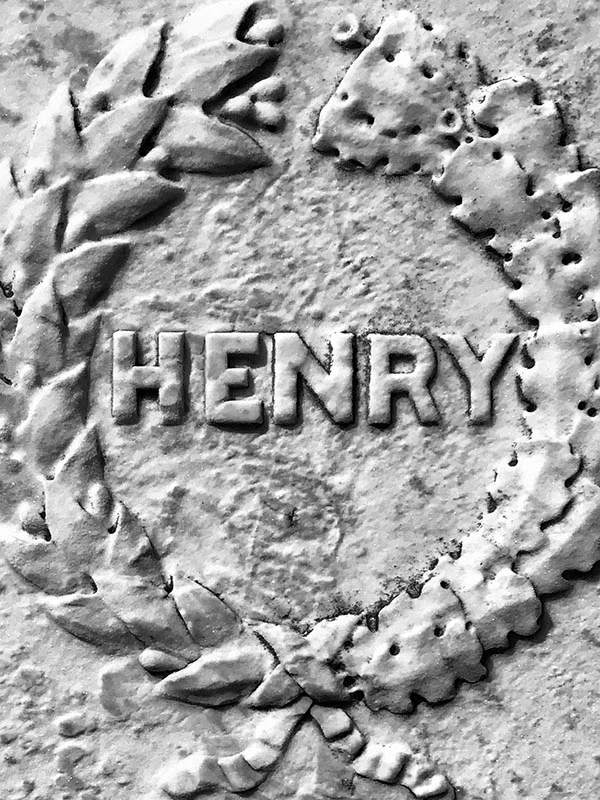

A Mysterious Cadet Death

A West Point cadet's strange death in 1849.

Recently, while walking through the West Point Cemetery, I found myself near the Cadet Monument in the area where early classes erected monuments to fallen classmates. One in particular reads:

In memory of William R. Henry of Indiana who drowned during his passage across Lake Erie August 23d 1849...

One would suppose a shipwreck or a steamer explosion, which was fairly common, or perhaps an accident embarking or disembarking, which was also common. But none of these explanations appears to have been the cause of Cadet Henry's early death.

In Hazzard's History of Henry County, 1822-1906: Military Edition, the author recounts William R. Henry's last day. He includes a letter dated August 24, 1849 from an H. Garrard (possibly K. Garrard the future Union General?) to Superintendent Henry Brewerton. It reads:

Captain Brewerton.

Dear Sir :— It is with much sorrow that I am compelled to write to you concerning the disappearance of Cadet Henry.

Mr. Henry and myself were on board the steamboat Queen City, crossing from Sandusky City to Buffalo. Last night just before retiring he requested me to awake him on our arrival at Buffalo. I went to his state room, on reaching this place, this morning, but his berth was empty, although all the clothes he had worn the previous day were as he had placed them on going to bed.

I remained together with Mr. Norris on board until every possible searchand inquiry had been made, but as yet nothing has been discovered concerning his fate. Mr. Henry's trunk is in charge of James C. Harrison, Agent Reed's Line, Buffalo, New York.

I have the honor to be Your obedient servant.

H. Garrard

Hmm. Suicide? Foul play? Maybe not. In the same history, author George Hazzard says that while Henry was on furlough before his death, he stayed at a hotel and woke up in a different room than the one rented to him. The author recounts, "Incidents of similar character showed him to be a somnambulist and his death, as related in the letter of General Miles, must doubtless be ascribed to this fact."

Death by sleepwalking! The West Point Cemetery has many tales to tell, but this is one of the most unusual I have come across. Rest in Peace Cadet Henry...

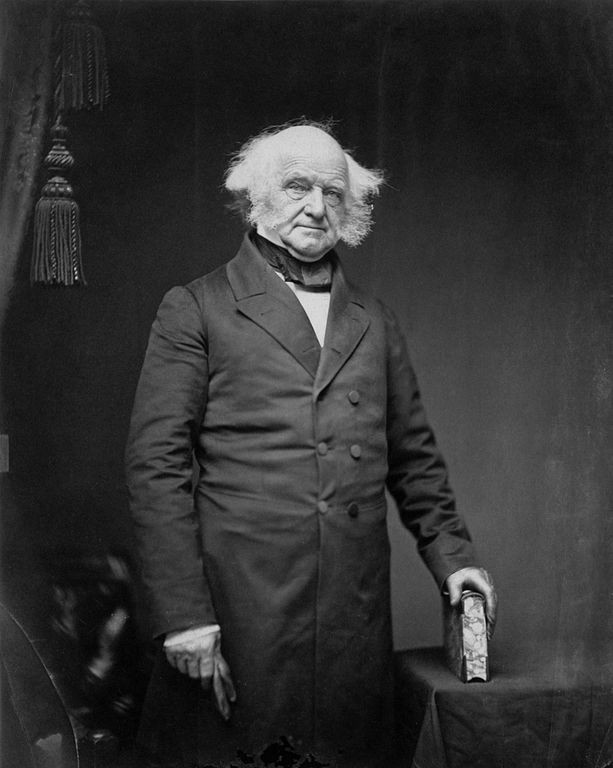

Martin Van Ruin Visits West Point

A short story about Martin Van Buren's 1839 visit to West Point.

Martin Van Buren in the 1850s. Photo by Mathew Brady.

Our first President not born a British subject was Martin Van Buren, a New Yorker from Kinderhook south of Albany. Swept in on the popularity of Andrew Jackson, for whom he served as Vice President, he soon was known as “Martin Van Ruin” when the economy crashed in 1837 and stayed in the gutter for the rest of his Presidency. He was trounced by Harrison in the 1840 election. In any case, Van Buren was the consummate politician in all the best and worst ways and was also known as the “Little Magician” for his political abilities (and short stature at 5’6”). In New York politics he was a giant and traveled the state regularly. In the summer of 1839, he visited West Point with Gen. Winfield Scott and Secretary of War Joel Roberts Poinsett. Van Buren’s son Abraham was an 1827 USMA graduate.

James Gordon Bennett, Sr., founder and publisher of the New York Herald.

Also at West Point during the Presidential visit was James Gordon Bennett, Sr., the famed publisher of the New York Herald. He had started the paper in 1835 and it skyrocketed in popularity (or infamy) in 1836 when the Herald covered the murder of Helen Jewett, a prostitute, in graphic detail. Bennett was also a pioneer in the use of graphics in his papers and is considered the first to conduct a Presidential interview for the media (with Van Buren). The Herald and its editor were popular and known to cadets. They could get newspapers and magazines delivered to the West Point post office.

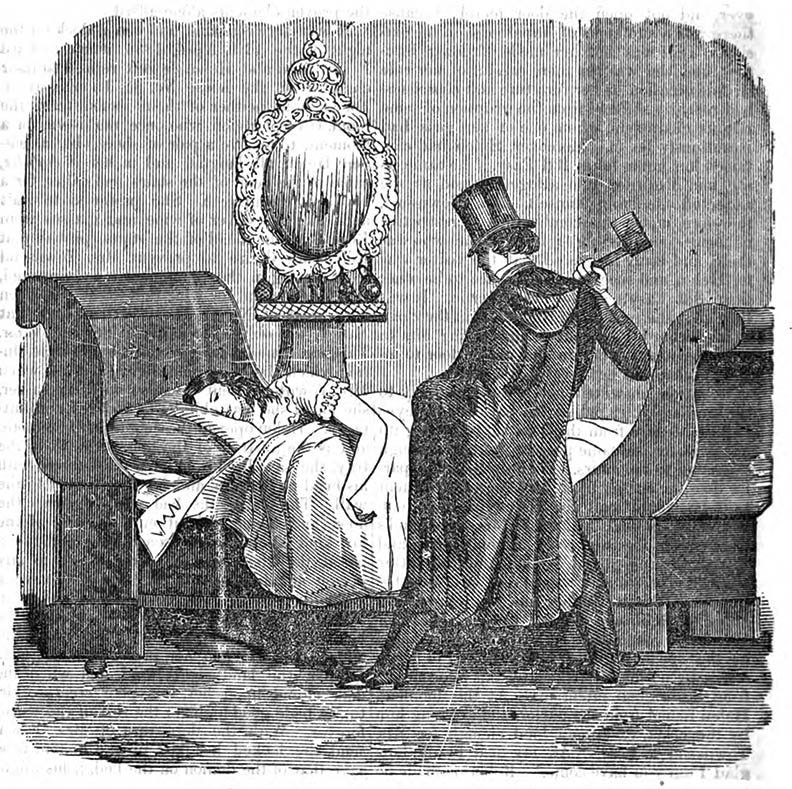

The murder of Helen Jewett as depicted in The Lives of Helen Jewett and Richard P. Robinson by George Wilkes, 1849.

As would be expected for a Presidential visit, there was pomp and circumstance. Three boats arrived at the West Point dock with the President and guests. Superintendent Richard Delafield met the guest of honor along with 30 cadets and the West Point Band. The party then walked up the hill to the Plain. The rest of the Corps was gathered in front of the Superintendent’s House for the National Salute. At the time, the Salute included one gunshot for each state which was 26 in 1839. The New York Herald reported the following account:

As soon as the President reached their front, a national salute was fired; and such a salute, God help us, was never fired before or since. It was bang—fiz—bang—pop—fiz—pop—bang—fiz—and so on along the line. The very devil seemed in the guns. The officers swore—the cadets sweated, and at last they fired the twenty-sixth gun—bang—and then another; the twenty-seventh gun went off with a loud report. “Stop that firing,” said Major Delafield, “and enquire what that twenty-seventh gun was fired for?” The officer went and returned, and reported that the twenty-seventh gun had been fired for Bennett’s Herald. At this there was a great laugh and commotion, and we were told that the cadet was put under arrest. (as reprinted in the Mississippi Free Trader)

Cadets always find a way to get themselves in trouble. Bennett did not support Van Buren in the 1840 election, so whether this story is accurate or a way of poking fun at the “Little Magician” will never be known. The National Salute was fixed at 21 shots in 1841.

Bonus Van Buren Trivia: In addition to "Martin Van Ruin" and the "Little Magician," Van Buren was known as "Old Kinderhook" because of his birthplace. During the 1840 election, Van Buren's supporters carried signs saying "OK" and it is believed this help popularize the term "okay" in the American vocabulary. More here.

Selected Sources:

Cohen, Patricia Cline. The Murder of Helen Jewett. New York: Vintage Books, 1998.

The Mississippi Free Trader. August 3, 1839, p. 2.

Lincoln's Secret Trip

Learn about President Lincoln's surprise trip to West Point.

In June of 1862, President Lincoln made a secret trip to West Point. Check out the video below to learn more and click on the YouTube icon at the top right of the page to go to our YT page and subscribe.

Tales of Ninny

Tales of cadet shenanigans from the 1830s...

Here's an account of a poor lieutenant named Ninny (real name Nathaniel Sayre Harris, USMA Class of 1825) and a few cadets that harassed him so much that he left the Army. Obviously, this would not stand today, but the story gives insight into cadet shenanigans in the early 1800s. The story involves Cadets Arnold Harris and Forbes Britton of the Class of 1834, as well as Cadet Benjamin (Benny) Roberts of the Class of 1835. Ninny was an Assistant Instructor of Infantry Tactics known as a disciplinarian fond of writing cadets up for violations (called "skinning" in the old days). What follows was published in a September 1878 issue of the Army and Navy Journal, complete with 19th-century words and grammar. The language is so fun that I thought it would be best to publish it word-for-word. When you're done, please share and consider joining our growing mailing list.

"Our three worthies hated Ninny with a hatred unspeakable, and they made his life a torment to him. One winter morning, when the reveille roll call was long before day light, Ninny was officer in charge, and he took his stand near the old North Barrack door and near the coal pile to see that everything went on properly. Benny Roberta spied him, and pretending to take him for a post he walked deliberately up to him, and he had commenced to put a serious indignity upon him when Ninny attempted to seize him. Benny had short legs, but he could run like a scared wolf, and he "lit out " with Ninny after him. He took down to the end of South Barracks, then around It and up through the Sally-port and over towards the North Barracks hall door. Ninny was gaining on him, when Benny threw his arm around a post near the coal pile fence and swung himself quickly around. Ninny was close after him, but in turning the post his sword got foul in some way and he fell. Benny was in the barracks in an instant and the chase was given up. Of course all made a great deal of fun, but it was very dark, and it is very doubtful whether any one in the corps knew at the time who it was that Ninny was after.

The barracks mentioned in the story were located on the Plain near the corner of the Library and Eisenhower Barracks. The North Barracks stuck out into the Plain towards what is now the baseball field. Ninny's quarters were located close to road in front of the West Point Club. Map by T.B. Brown, 1826. Annotations by the author.

Troublemaker Benny Roberts later in life. His highest rank was Brevet Major General (1865).

"Now Ninny knew that there were only three c1dets lo the corps that could be guilty of such a piece of impudence. But these fellows were all about the same height —and it was too dark to discover any features. Major Fowler was the commandant or cadets, and when the office hour arrived each of the three was sent for in turn to come to the commandant’s office. Ninny was then trying with all his might to see something that could enable him to say positively which was the culprit. But each one of the boys kept a countenance as serene as that of a mummy, and Ninny gave It up. I rather think that affair had something to do with his leaving the Army, which he did soon after this event. He took refuge in holy orders lo the Protestant Episcopal Church. In after years Ninny would come occasionally to officiate in the cadets’ chapel, and his appearance would always revive the old story of his foot race with Benny Roberts.

"Ninny occupied as his quarters a small building lo the eastward and about eighty yards from the old North Barracks [Note: sometimes called "Castle Harris"]. This building had previously been used for baser purposes, and some years afterwards It was used as the barber shop and boot black room, and still later it was used by Jo Simpson as an ice cream and refreshment room. It was a circular or octagonal shaped building with a cupola. Between this building and the North Barracks was a high stone wall which prevented a view of the windows of the lower floor of the barrack. Now, our worthies had transformed their brass candle sticks into small mortars, and by charging their old bell buttons they made of them miniature shells, which they could fire from the windows behind the wall, and they had struck the range so accurately that they could burst a button shell over Ninny's quarters any time. Occasionally a bombardment would commence along the whole line of windows, and Ninny's life was made so uncomfortable that he was obliged to change his quarters. But the event that immediately brought about the change was this: One morning at reveille the whole corps of cadets were astonished to see Ninny, in full tog, standing on the top of his quarters, leaning very composedly against the cupola, quietly surveying the surrounding scenery. Those who were not lo the secret of the affair suspected that he had taken his stand there in a fit or insanity. It was soon observed, however, that the figure did not move and that it was not Ninny, but at a little distance it was his vera effigies. Some one whom no fellow could find out had gotten into the quarters and stuffed a suit of uniform so cleverly that the resemblance was perfect, and placed it on the top of the building. This was too much for human nature to stand and the building had to be vacated."

Poor Ninny! I feel bad for him. Arnold got out of the Army after three years. Britton served sixteen years before becoming a state senator in Texas (Blutarski-esque). Benny Roberts served four years, got out, then entered service again. He earned the rank of Brevet Major General. Ninny's Cullum entry is here.

Primary Source: "Two Army Characters," Army and Navy Journal, September 14, 1878.

Aeronauts at West Point, 1906, Part 1

West Point's first balloon flight, 1906.

February 11, 1906 was an exciting Sunday at West Point. On a cold but clear winter afternoon, the Academy witnessed its first balloon flight. Ballooning was all the rage in Europe but enthusiasts in America found little public interest. In 1906, several French balloonists came to the States to put on flying displays on behalf of a new organization, the Aero Club of America. Their first flight was at West Point.

Charles Levee lifts off from West Point on 11 February 1906. The photo is taken near the corner of what is now known as the Firstie Club looking up the hill. The Battle Monument can be seen on the right side of the photo near the chimney of the building. Source: Collier's, 24 February 1906.

The aeronaut for the day was Charles Levee, a young Frenchman. His balloon, called the "Allouette" (the "Lark"), was a 28' in diameter cotton sphere with a capacity of 12,500 cubic feet. It took about four and a half hours to fill the craft with coal gas. [Coal gas was used to heat and light communities before natural gas.] This was completed below the Ordnance Compound (today's Firstie Club) near the Post's gas works using 2-inch copper tubing. One observer notes having to walk around in the snow in an attempt to keep warm during the lengthy prep time.

At 3:30, the balloon was filled with coal gas and ready to fly. It was moved to the siege battery on Trophy Point where the bandshell now sits. After a small trial balloon was put up to check wind speed and direction, Levee climbed aboard with 150 pounds of sand as ballast and started his ascent, saluting a large gathered crowd in both French and English. There had been a hop at the Academy the night before and many chaperoned ladies were in attendance. Because the weather was cold and the Hudson frozen, some onlookers had walked across the ice from Garrison or Cold Spring.

The balloon rose up to over 2,000 feet and started north towards Newburgh. The crowd watched as long as they could see the balloon silhouetted against the cold blue sky. Eventually, they lost sight of the craft, but Levee's trip continued. He kept going and going, eventually traveling in pitch black darkness without any knowledge of the Hudson River Valley's topography or settlement patterns. He later claimed to have reached 8,000 feet. His flight came to a bumpy end in Hurley, NY, near Kingston, a full four hours and 35 miles from USMA. The Wilkes-Barre Record reported:

Levee's flight, 11 February 1906.

Levee had counted on a clear moonlight night, but the shift of the wind brought a mass of vapor over the balloonist's head, completely obscuring the light upon which he had depended to aid him in his flight....

Towards 8 o'clock in the evening Levee decided to land. he was shrouded in ink-like darkness. Peering over the side of the car, he was unable to tell whether he was sailing over land or over the Hudson. Then far below he saw a light. At this time the balloon was settling at an angle of about forty five degrees.

Levee shouted at the top of his voice in order to arouse the people in the houses, but the wind carried the sound away. There was still one bag of sand in the car, which he was about to throw over the side in order to rise for a time and make his descent later, when a rift in the clouds enabled him to see that he was sailing over a clear place, which was just where he wanted to land. Pulling the rip cord, which split the great bag in two, letting out the gas with a rush, Levee clung to the guy ropes in expectation of a shock. It came when the car struck the earth with a thud. But Levee was unhurt, and the when the grappling anchor held the plucky aeronaut spring lightly to the ground after having sailed over the earth for the better part of four hours.

Can you imagine how the locals reacted when an aeronaut landed in their field on a cold February night?

Levee returned to West Point for another voyage, but we'll leave that to another post...

Selected Sources:

"Aeronaut in Flight over Hudson River," New York Times, 12 Feb 1906.

"Ascensions Made by Members of the Aero Club of America from Formation of Club to Date," Monthly Weather Review 906, June 1906, pp. 280.

"Four Hour Voyage in Air," The Sun, 12 Feb 1906.

"Levee Lands Safely," The Wilkes-Barre Record, 13 Feb 1906.

"What the World is Doing," Collier's, 24 Feb 1906.

A Cadet Casino Christmas, 1890

A cadet outing on Christmas Eve in 1890.

For much of West Point's history, cadets were not allowed or able to go home for the holidays due to rules and distance. Because of this, other activities took place, both organized and unorganized. The 1826 Eggnog Riot was certainly one of the more infamous unsanctioned events! In 1890, some cadets were allowed to go to see a Broadway show called Poor Jonathan at the famed Casino Theatre on Christmas Eve. The reason for this special event is that the musical comedy's third act took place at West Point. The Sun newspaper of New York reported:

The Casino Theatre. Date Unknown. Source: Library of Congress.

The youngers in the Military Academy at West Point came to town last night to have a Christmas Eve jubilee at the Casino over the West Point scene in "Poor Jonathan." The West Point cadets were there in their uniforms of gold and gray, and some of the Annapolis cadets were there, too. The naval cadets occupied seats behind the West Pointers. There were seventy in the party. They rose in a body and cheered the chorus girls who execute the military march.

Poor Jonathan had a complicated plot involving a servant, Jonathan, who accidently puts soap in an ice cream dessert at a dinner party. Jonathan falls in love with a fellow servant, becomes rich when his boss feels bad for him, etc. etc.. In the original German version of the show, the final act involved African-Americans picking cotton along the Hudson, but it was thought that this would not play well to a New York audience. Rewrites moved the final scenes to West Point, hence the mention of chorus girls doing a military march. There was apparently a beautiful panorama of West Point revealed at the beginning of the final act that elicited so much applause on opening night that the show was delayed.

Lillian Russell. Source: New York Public Library

The female star of the show, and many productions at the Casino, was Lillian Russell, a star of the era. She is remembered today both as a performer and as the longtime companion of wealthy businessman Diamond Jim Brady. In 1895, Brady would become the first New Yorker to own an automobile. He was known for his incredible appetite and love of gambling. The day after the cadets visited the Theatre, photos of Ms. Russell were among gifts being handed out in honor of the holiday.

The Casino Theatre was built in 1882 as a grand example of Moorish architecture. It was one of the first completely electrified buildings in the City. and was a very popular venue for operettas and musicals. It closed in 1930. Read more about the Casino in this excellent article.

Selected Sources:

"Cadets See 'Poor Jonathan.'" The Sun . December 25, 1890.

"Poor Jonathan." The World. October 15, 1890.