Getting to West Point, 1824

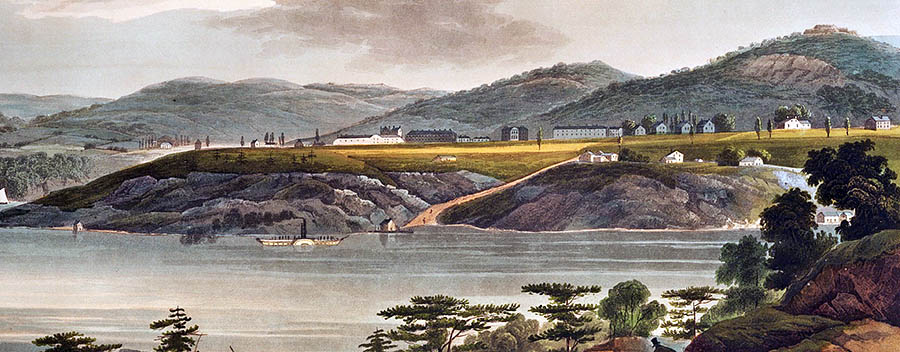

West Point ~1820. Source: NYPL Digital Collections

Last year, I posted the West Point arrival story of John H.B. Latrobe. Check it out here if you missed it. For this R-Day, I post the rather lengthy arrival story of Albert Church. Class of 1828 and future USMA Professor of Mathematics. Church was just 16 when he entered on a Sunday in June of 1824. At the time, there was no R-Day because cadets could not be expected to arrive on a particular day because transportation was so difficult. Instead, they were given a time period in which to report, so new cadets arrived in dribs and drabs. Church was from Connecticut. Years later, he recalled his first day:

Having failed to connect at Poughkeepsie with the only passenger steamer then running every other day on the river, I took my passage on a sloop, a regular packet for New York, with the promise that I should be landed at West Point, though this was not a prescribed landing place. This promise, better performed than many promises made nowadays, resulted in my being put ashore at 3 o'clock in the morning at Cold Spring, in a pouring rain. Wet to the skin, I found my way to a hotel, where I impatiently waited the coming dawn and then sallied forth, in search of transportation to West Point. At the wharf I found a small sail boat freighted with a pair of black horses, just ready to cast off. Stepping on board—myself and traveling companion lugging my blue chest, the modern army trunk was not then in vogue—we were soon set down on the North wharf, then the only one in use. A sentinel, in full uniform; the only human being in sight, brought me to, and required, me to write my name on a slate—a habit which for many years was strictly enforced on all coming to or leaving the Post. Upon making inquiry how we were to reach the Military Academy, for I had no idea how far we were to go, who said in a jocose manner, that we should have to walk, unless we could persuade the owner of the ponies to let us ride them up the hill. As for the chest, we could take that up ourselves, or leave it for the authorized porter, (an old soldier with one arm, the lost one being replaced by an iron hook suitable for his business,) no other person being allowed to transport baggage for hire; that he might be around in the course of the morning, but probably I should have to wait till Monday morning—a pleasant prospect for a fellow without a dry thread about him. By the way, I should say that I believe; these black horses were, at that time, and for two or three years after, the only span of matched carriage horses on the Point. They belonged to the Postmaster and were always, during these years, pressed into service to draw the various dignitaries who visited the place, up the hill, among others, in two instances, General La Fayette. At this time too, I think none of the Professors or Officers owned a horse. There wore no roads suitable for carriages scarcely so for horseback rides....

The sentinel having pointed out my way up the hill, old road still visible just below the present one, I crossed the plain diagonally, just after reveille, and passed between the two most prominent buildings of the academy, the North and South barracks, without seeing an individual, until I entered Gridley's hotel, a large two story wooden house on the edge of the bank, a little of northeast of the present new building for public offices [note: this refers to the 1870 Administration Building]. Here I found several other young gentlemen ambitious of military fame. This was the only hotel in the neighborhood, "where all visitors were entertained, except special official ones, who were cared for in the west end of the cadets' mess-hall, by Mr. Cozzens, the famous ancestor of the after Cozzens' hotel keepers. Having relished a good breakfast, four young aspirants took their way back and across the plain...

Having reported to the Superintendent and been received and questioned with that kind, yet unbending dignity for which he was ever distinguished, we were escorted by an orderly to the South Barracks, and the last three described were located by the cadet officer in charge of the new cadets, in a small room without vestige of furniture, with no place to sit except on the window sill, and left without a word of direction or advice, to discuss among ourselves what was to come and what we were next to do. Upon hearing a drum and a running to and fro, we concluded something of importance was going on, but had no idea whether it concerned us or not; until the cadet lieutenant, who had located us and so kindly left us to ourselves, rushed into the room and with an angry tone demanded, "Why do you not fall in?" Now I understood the meaning of the word "fall," but into what, or from whence, we were to fall I did not know. Of course we started forth and down the stairs we went, and came near falling, literally into a heap at the bottom. Fortunately, however, we fell into the ranks already formed for church, were faced to the right and told to "forward march." At my first move, I stepped squarely on to the heel of my forward file, when he faced about and with doubled fists threatened serious war, before I felt myself sufficiently educated for it. I took a backward step, not laid down in the Tactics, when those familiar cries, "pay attention," "close up," "what are you about there," had the effect of restoring order. Poor marching soon brought us to the chapel, where after a long preliminary service I listened to a dull sermon, one hour and a quarter long, the only lasting effect of which was to lay the foundation of that dislike, which I have ever since entertained, for long sermons.

The South Barracks, where Church was housed on arrival, had 48 cadet rooms, most holding three cadets. It was a gray stone building with a slate roof and verandas on both sides. This image shows spiral staircases up the front, but these were likely added after Church's era.

Upon leaving the chapel, with strong convictions that this kind of life was not suited to my taste, and that, doubtless, I had mistaken my profession and had better set out for home on the first arriving boat, I was cordially greeted by a cadet of the third class whom I had once before seen, who took me to his room and introduced me to his roommates, members of both the second and first classes. These cadets, instead of making me stand on tip-toe on one foot, tossing me in a blanket, or smoking me out, treated me with kindly interest, gave me correct information of what I was to do, and how to do it; in other words, treated me as a true gentleman ever treats his fellows, and thus seriously modified my resolution to go home. In the meantime, the rain which had been falling continually, ceased, the sun shone out brightly; on my return to my room I found my chest, got out of my wet clothes, and intelligently fell in for dinner with pleasant thoughts and coming appetite.

Church's entire memoir is available from the USMA Library here.

This map, a crop of an 1826 map by T.B. Brown, shows many of the locations mentioned by Church. Source: Library of Congress

Source:

Church, Albert. 1879. Personal Reminiscences of the Military Academy from 1824 to 1831: a paper read to the U.S. Military Service Institute, West Point, March 28, 1878. West Point: U.S.M.A. Press.